Ashtead Technology - Thesis Update: answering key investor concerns.

As I mentioned in my previous blog, Ashtead reported a 6% decline in pro-forma revenues in its half-year trading update. Investors were understandably disappointed with the news, which was a surprise considering the business has generally been ticking along at double digit organic growth. The share price dropped 25% on the news which is particularly significant given the share performance has been fairly poor against the backdrop of fairly strong fundamentals.

I have actually used the opportunity to increase the size of my position, and I am tempted to add to this even further if the price continues to decline. Before doing so, however, I think it is sensible to look at some of the concerns investors seem to have and whether they have any real merit.

Misunderstanding around the offshore wind story

Ashtead’s long-term growth story is predicated on the idea that offshore wind will form a meaningful part of the transition to cleaner energy. However, concerns around the economic viability of offshore wind have been around for some time now. Add to this the impact of inflation, higher interest rates and supply chain challenges pushing project costs up by 30-40% and it is easy to see why many are pessimistic about its long-term prospects.

For the first time, auctions for offshore wind projects in the UK (2023) and Denmark (2024) received no bids; spiralling costs and insufficient pricing kept companies from investing in new sites. Several operators have also exited existing projects including Norway’s Equinor, which withdrew from projects in Vietnam and Spain, and Orsted which cancelled its Ocean Wind 1 and 2 projects off the coast of New Jersey. More recently Orsted halted its Hornsea 4 project which was set to become one of the largest in the UK.

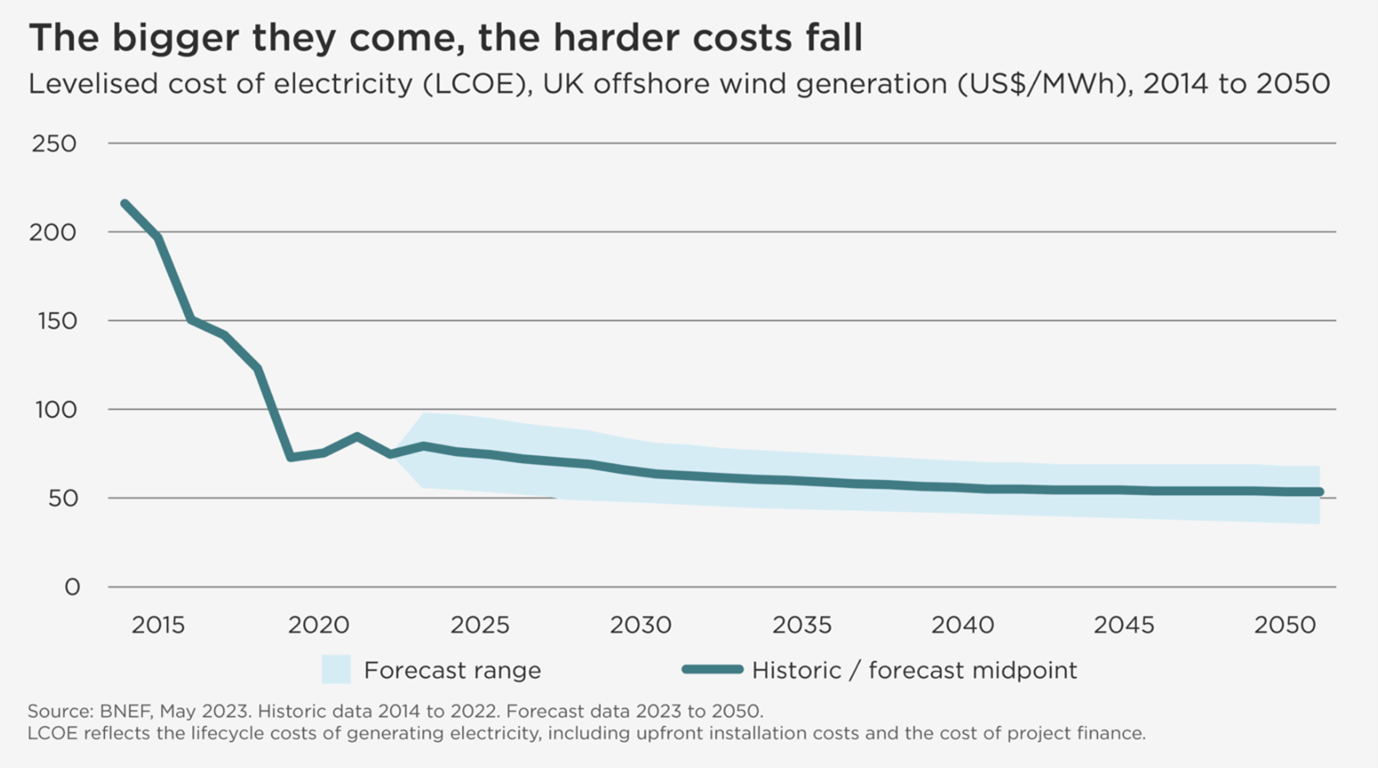

One of the key factors in determining the suitability of energy projects is the levelized cost of energy or LCoE. Essentially this measures the average cost of producing one unit of energy, typically MWh, over the lifetime of a project. Estimates vary significantly, but the current LCoE for fixed-bottom offshore projects in the US is around $117/MWh, and closer to $44 in the UK.

Opponents of offshore wind have several complaints. Firstly, there is the challenge of newer projects being further out to sea; because these will require greater levels of infrastructure spend, such as cables and foundations, they are likely to be more costly than current projects. There is the prospect of floating offshore wind, but the technology is still relatively nascent, and it has far higher LCoE’s than fixed bottom, at an estimated $181/MWh.

Offshore wind is also intermittent, meaning that it requires supplementation from more consistent sources of energy. It also requires the use of large batteries to store electricity and release it onto the grid at the correct times. The degradation of turbines is another issue for offshore wind, with the performance for large turbines decreasing by 4.5% per year; this means that after 10 years their output is close to half its initial value.

Offshore wind, therefore, has a number of significant challenges from an economic standpoint. Despite this, it still has a crucial role to play in the transition to net zero. It is amongst the least carbon intensive forms of renewable energy, beaten only by onshore wind. It is worth pointing out here that whilst onshore wind has an LCoE roughly half that of offshore, in smaller countries like the UK there is simply not the space to build enough projects. Onshore windfarms also typically face far greater levels of opposition than offshore, and their generating ability is lower due to slower wind speeds (a windspeed of 15mph generates twice the energy than one of 12mph).

Whilst in countries like the US, with its abundant oil reserves, the cost of generating energy through gas combined cycle is generally lower than renewable sources, this is not the case in countries like the UK. A 2023 report by the UK Department for Energy Security estimates that for projects commissioned in 2025, offshore wind will have a LCoE under half that of gas, beaten only by onshore wind and solar. What is also interesting is how this is forecast to change over the next 15 years, with the LCoE for gas rising to £179/MWh, compared to offshore wind which is forecast to remain stable at around £41/MWh. This story is the same for a number of other countries who rely on imported gas such as Denmark and the Netherlands.

Source: Department for Energy Security & Net Zero

Source: Department for Energy Security & Net Zero

The UK renewable auctions use a system called Contracts for Difference (CfD) which helps to stabilise revenues for the generator and reduce risk for investors. The failure to attract any bids during the 2023 auction was the result of the strike price being set too low against the backdrop of significant cost increases during 2022. The UK increased strike prices for the 2024 auctions to £73/MWh for fixed offshore and £176/MWh for floating. Given that the cost of gas still remains significantly above the strike price for fixed offshore wind, and current wholesale spot prices are between £70-£75 MWh in the UK, there is still headroom for further price increases.

Because of the commitment to reaching net zero by 2050, most countries also don’t have a choice as to whether they support these technologies. The gradual phasing out of oil and gas must be replaced by renewable alternatives. Solar and onshore wind, as the two-most cost-effective solutions, are obvious choices, but as discussed are constrained by space in smaller countries. Nuclear will undoubtedly have a role to play because of its ability to generate energy irrespective of wind or sun, but the cost is high; current estimates for the UK between £60-£100/MWh and approximately $118/MWh in the US. Projects also often face significant opposition from local residents.

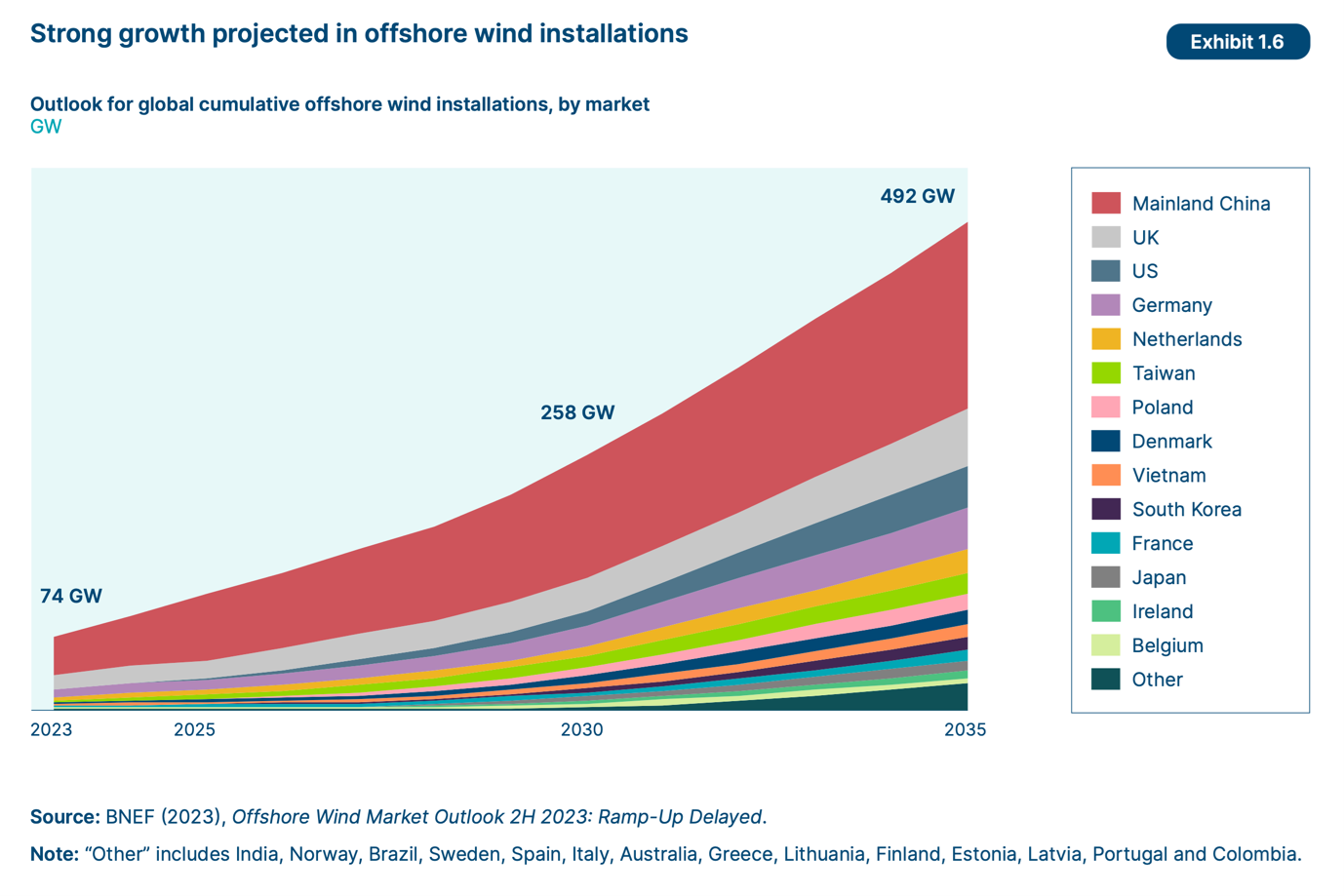

Countries will therefore need to utilise a range of different renewable energy sources. Whilst cost will remain an important factor, these technologies are likely to be heavily subsidised in order to achieve the ambitious targets. Offshore wind, despite the undeniable economic challenges, is low carbon, faces minimal backlash (especially as projects move further out to sea), and has a greater load factor than onshore wind. If we look at the capacity projections for a range of countries, we see that even missing their published targets, capacity is expected to at least double for most countries over the next 5 years.

Source: Energy Transitions Commission

Source: Energy Transitions Commission

Government support will form an integral part of achieving this. In the UK, the government has already committed to raising strike prices for next year’s auction by 11%, to £81/MWh. Other changes, such as allowing projects without prior consent to participate in auctions, are all aimed at driving growth. France has recently raised its offshore capacity target to 18 GW by 2035 and is investing €10.82 billion to support two projects. Denmark is also set to return to subsidised support for the offshore wind sector in an attempt to mitigate the cost challenges currently faced by the industry. This story is the same for other countries including Japan, Taiwan, Poland, and a number of others.

One of the only places where this is not the case is the United States, with Trump signing an executive order pausing all federal wind permits. Whilst this is significant for US offshore wind, it is largely insignificant for the global industry for the following reasons. Firstly, the US just isn’t a big player. The combination of a large land mass providing the opportunity for cheaper onshore projects and the abundance of oil & gas at much lower costs ($38.07/MWh) than other countries mean it is not an essential part of the US’s energy mix. Secondly, his power is limited. His attempts to stop the existing Empire Wind 1 projects were stymied by a combination of legal and political pressure, so he is only able to halt new greenfield projects. Finally, given the significant bottlenecks in the supply chain currently, new projects do not necessarily mean more work, at least in the medium term.

There are also likely to be significant cost reductions from current inflated levels. If we look at the below waterfall graph showing the cost increases for offshore wind, we can see that a significant amount is related to higher interest rates. Consensus is that there will be rate cuts towards the end of this year, helping to bring down the cost of capital for these projects.

Source: Energy Transitions Commission

One of the other biggest causes of bottlenecks in the offshore supply chain is the shortage of boats. Specifically, wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs) that are capable of handling the much larger, next generation turbines. The daily cost of renting these vessels have skyrocketed in recent years, with average daily costs reaching $300,000 and expected to rise further. The below graph is from a Wind Europe report published in 2022, stating that the current number of existing and forecast boats would be insufficient for the global demand, particularly towards 2029 and 2030. According to this report, only one new WTIV would be built in 2025, but current figures suggest that at least 6 are now set to be completed this year, so demand is filtering through. A number of suitable vessels are also being used by the offshore oil industry, where higher wholesale prices mean better returns. Higher contract prices for offshore wind should therefore make it more competitive with oil and gas and help shape asset allocation between the industries.

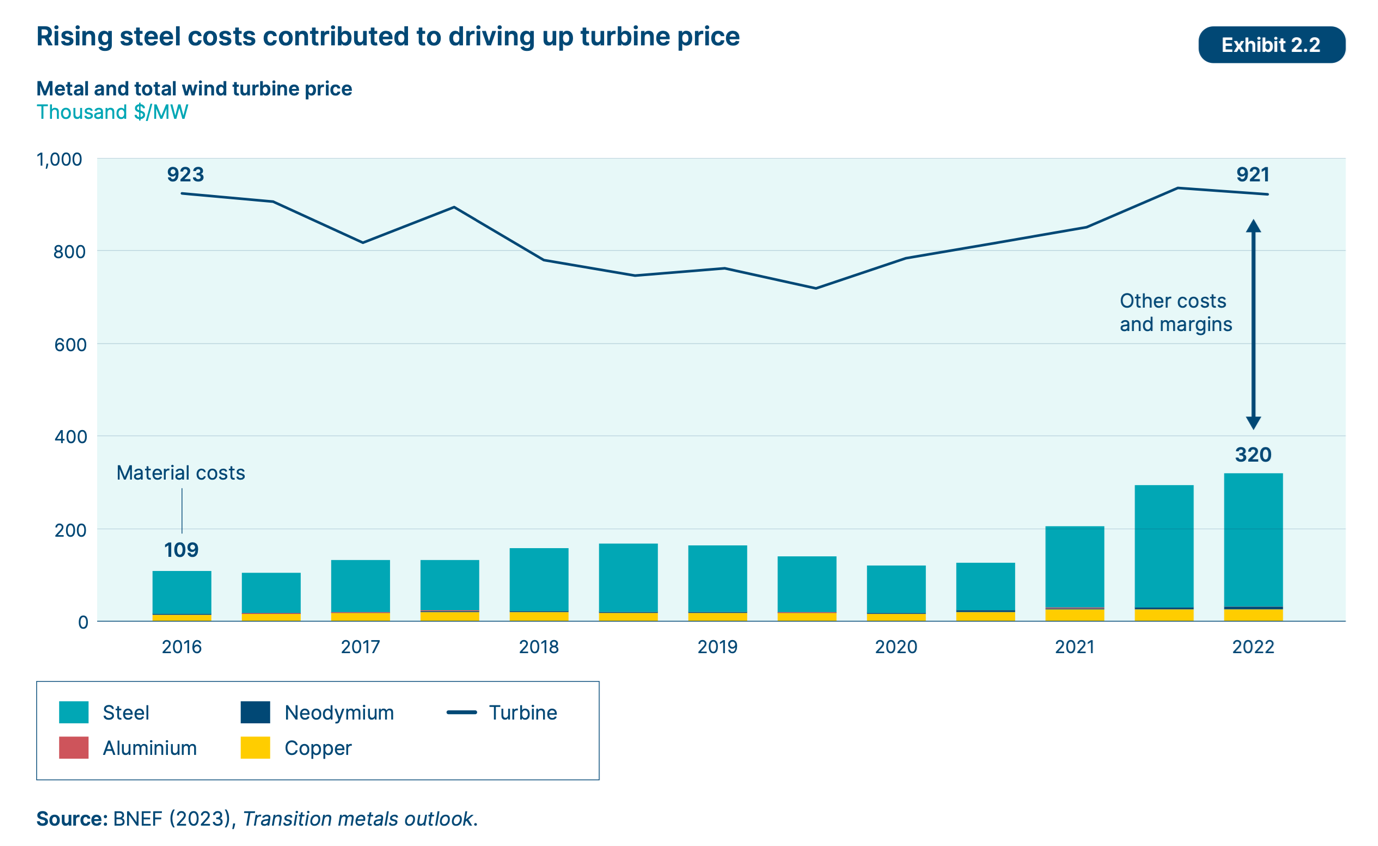

One of the other issues affecting project costs have been increases to turbine prices, which had otherwise been on a steady decline for the last decade. The primary cause of this has been price increases for materials, particularly steel and rare earth metals like neodymium.

Source: Energy Transitions Commission

Steel, in particular, increased in price dramatically during 2022 but has since come back down to 2020 levels. Rare earth permanent magnets, which form a crucial part of wind turbines, are predominantly produced in China, putting supply at risk. That said, China would be shooting itself in the foot if it refused to export these metals, and there is likely ample supply even for its burgeoning offshore industry. Other advancements in technology such as wooden pylons will also help to ease the pressure on steel requirements, although the technology is relatively new at this stage.

Constant increases to the size of turbines over the last decade have also made standardisation, and therefore economies of scale, difficult to achieve. The rate of technological advancement, particularly related to size, is likely to begin to slow; the challenge of transporting larger turbines out to sea means there won’t be demand for turbines above 20MWh until suitable ships have been developed. This should allow for greater standardisation of parts which will in turn drive further cost savings.

The final point that I think critics of the industry are missing is that if there are sufficient incentives and capital flowing into the industry, innovation is likely to drive further cost reductions. There are already examples of this. Maersk’s new WTIVs, which features a separate installation and transport platform, enable the installation deck to remain out at sea whilst new turbines are collected from shore; these are forecast to increase the efficiency of installation by up to 30%. Wooden pylons are also now being utilised in some projects, with their construction lighter and more sustainable than steel. If we look at the LCoE for the UK offshore wind industry, which serves as a good barometer because of its relative maturity, we see that it has declined markedly over the past decade as improvements in technology and cost have filtered through.

Cyclicality in oil and gas

Higher oil and gas prices mean greater levels of activity in the O&G sector. This is because higher prices mean better returns, helping to de-risk future investments which in turn incentivises companies to take on new projects. This raises concerns for investors in Ashtead over the impact that declining oil prices could have on activity in their oil and gas segment.

Graph showing oil and gas prices over the past 30 years; oil is blue, natural gas is orange.

The oil and gas markets have always been highly cyclical. If we look at the price for both crude oil and natural gas over the past 25 years, we can see that there have been massive fluctuations during that period, often linked to economic cycles (the grey areas show periods of recession). The recent decline in oil prices from the 2022 peak could be causing concern for Ashtead investors who assume that activity in the sector, specifically offshore, will decline in tandem with price.

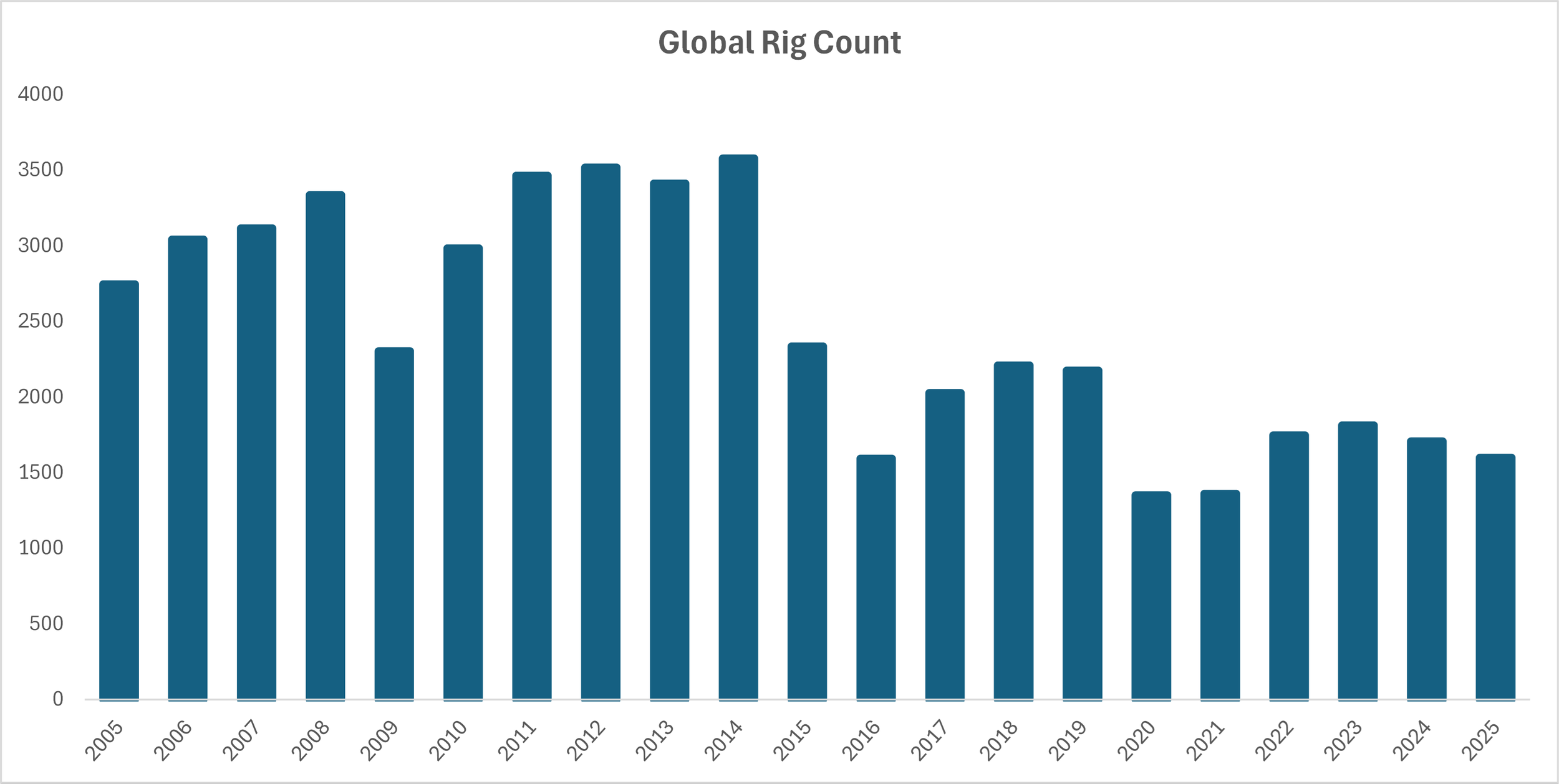

I don’t think this is a significant cause for concern for the following reasons. Firstly, oil & gas companies have been far more measured during the most recent up-cycle. If we look at the below chart showing the number of global oil rigs, we can see that during the build-up to the 2014 oil crash, E&P companies expanded their capacity at rapid rates. When oil prices collapsed, these companies were operating with far too much capacity and their returns suffered. If we look at the more recent period between 2020 and 2022 where oil prices again rose at rapid rates, the corresponding increase in global rig count was far more measured. We are therefore much more likely to experience a plateau rather than a real downturn in global O&G activity during this period.

The other factor that benefits Ashtead is the growing importance of offshore for oil and gas production. Although the vast majority of rigs are still located onshore, the larger oil & gas fields are now located at sea. This means that the majority of new oil discovered is also now offshore, as shown in the graph below. According to Rystad, offshore will account for 68% of all sanctioned oil & gas during 2023 and 2024. Another factor driving E&P companies offshore is the lower emissions per barrel compared to onshore, primarily due to greater levels of productivity. For this reason, although we may see some cyclicality for the oil and gas industry in general, offshore, and therefore Ashtead, are likely to be somewhat insulated.

Demand for oil and gas is likely to remain elevated in the short to medium term, playing a crucial role in the transition to net zero. Research from McKinsey suggests that global demand for energy will continue to grow by 3-4% until 2050. Even in scenarios where companies manage to achieve their net zero ambitions, demand for oil and gas is therefore likely to remain elevated for at least the next 5 years and likely much longer.

How this affects Ashtead

Up to this point I haven’t really mentioned Ashtead specifically, instead focusing on the markets more generally. Offshore renewables made up 28% of Ashtead’s FY24 revenue, slightly below the previous year. Whilst this is a significant percentage of its revenue, it is dwarfed by the contribution from oil and gas which is still growing at a rapid rate. Looking at the TAM for the business, broken down by segment, we see that offshore wind is the fastest growing but not the largest.

Most of Ashtead’ s customers are involved in projects across both the oil & gas and offshore wind industry. If we think about the current industry dynamic where the large vessels required for the installation of turbines are being used at offshore oil & gas rigs instead, we see that returns are likely to drive asset allocation between the sectors. The majority of Ashtead’s equipment (85%+) is fungible and can therefore be used across either sector. If we see government support driving greater allocation of resources to offshore wind, then we are likely to see corresponding changes to Ashtead’s revenue contribution. This is important because it gives them a somewhat hedged position within the offshore energy market and allows them to diversify their industry specific risk.

Ashtead also provides equipment used in the decommissioning process. As we can see from the addressable market graph above, this segment is forecast to be the second fastest growing, led by the decommissioning of oil and gas assets. Most countries have laws around the safe decommissioning of offshore infrastructure, so this area of the business should provide a stable source of income for the group. It also provides the group with some protection in the event of a material decline in oil & gas activity that is not directly offset by an increase in offshore wind.

Moving onto the concerns over Trump and his wind policy changes, the impact of this is not likely to be significant. Ashtead has only low single digit exposure to US offshore wind and has managed to perform well during previous periods of US offshore underperformance. In terms of the impacts that tariffs may have, this is harder to quantify. The general loss of confidence that this seems to have inspired is likely to be the primary driver in the slowdown Ashtead is currently experiencing. What does give me confidence here is that Ashtead’s end markets are both essential in the transition to net zero and are therefore likely to experience strong government support.

Finally, the record backlogs are an indication of the demand there is in the market for offshore contractors. It also means that whilst cancelled offshore wind projects are bad for the industry as a whole, Ashtead is likely to have a significant order book to fall back on. Despite this, in order to achieve its growth ambitions, subsea contractors will have to find ways to boost their capacity and reduce the bottlenecks currently stifling growth.

Conclusion

I have refrained from making this a full investment thesis, instead focusing on answering some of the key concerns that investors have with Ashtead. For me, I think Ashtead occupies a really interesting position in the market. It is the clear market leader and competes primarily with its customers who would rather rent from Ashtead than buy the equipment themselves. The current sell off has provided a really attractive moment to buy into the company, with the long-term market fundamentals remaining very strong in my opinion. Whilst the current impact of Trump’s trade policies and the general uncertainty this has created might cause problems in the short-term, in the long-term I believe the business is well placed to capture a significant part of this growing market.