The Gym Group: a low-cost operator with significant barriers to entry.

I am slightly changing the format of my write-ups here, and will now present the conclusion at the bottom, rather than as part of the summary.

Introduction

This is a company that I have loosely followed for some time now, having been initially impressed with their strong revenue growth out of COVID. Now I have looked at the business in more detail, I can see that it is operating in a fast-growing segment of an attractive market, and the business has a number of competitive advantages and barriers to entry that make it a potentially very exciting investment.

This will be one of the easier business models I have explained. The Gym Group (TGG) is a low-cost gym provider which operates over 250 gyms in the UK. The majority of their gyms are open 24/7 and are available through no contract memberships.

Why the opportunity exists

Unlike the majority of my other investments, this one was not prompted by a significant decline in the share price. Looking at a 5-year chart, we can see that the business is well below its 2021 peak, but its share price performance has been good during the past year, up 35%.

That said, I still think that the business is materially undervalued, and I believe that the following factors have contributed to this.

History of public market gym failures – High-profile failures during the late 90s and early 2000s, including Fitness First and LA Fitness, have tainted some investors’ perceptions over the attractiveness of gyms as investments.

Historically unattractive investments – Gyms have historically been seen as unattractive investments, with low barriers to entry, price sensitive customers, and capital-intensive business models.

Misunderstanding of the low-cost model – People see the low-cost segment as identical to the mid-market operators that struggled as publicly listed companies. However, as the founder of Gym Group says, there is as much similarity between the two as there is between Easy Jet and British Airways.

Difference between cash rents and IFRS 16 – The updated lease accounting conventions mean that current lease depreciation is higher than the cash rents the group pays on sites. This is expected to normalise during FY25 and then move below cash rents, although the effect could be delayed by the rollout of new sites; in the long-term, however, it should lead to significant margin expansion.

General UK market underperformance – Given this is featured in every one of my theses, I will not waste any more time explaining it here.

Thesis Summary

Market Dynamics

Growing percentage of the UK population are gym users – The penetration rate for gym members in the UK is currently 16.6%, well below that of the US and some Nordic countries which is closer to 20%. Several factors are driving further penetration including greater understanding around the importance of exercise, younger generations’ greater affinity with the gym, and the effect of social media on body image. All of these trends are expected to become increasingly prevalent over time.

Low-cost gyms are driving growth across the sector – The majority of growth within the gym sector is being driven by the bottom end of the market; low-cost share was 4% in 2012 but now stands at 28%. This growth is being driven by customer’s increasing preference for value and the erosion of mid-market’s relative value proposition.

Significant white space for low-cost operators – An independent report published by PwC indicates that there is still a significant amount of headroom in the UK low-cost gym market, with the potential for another 550-800 more sites. The Gym Group (TGG) is well placed, as the second largest operator, to capture a significant amount of this potential market.

Company Specific Factors

How The Gym Group offers low prices – TGG, and other low-cost operators, keep prices down by offering what they describe as a “no frills gym experience”. By reducing the initial fit-out costs, keeping staffing expenses to a minimum, and operating round the clock, they are able to offer significantly lower headline rates.

Scale advantages for the low-cost operators – The group’s scale gives it a number of advantages over smaller competitors. These include greater buying power, which translates to savings of approximately £150,000 on new sites, greater marketing spends, the ability to offer multi-site access, and greater negotiating strength for new sites. The combination of these factors creates significant barriers to entry for new competitors.

Availability of attractive ex-office and retail spaces – Both TGG and PureGym took advantage of the abundance of attractive units post 2008, enabling them to grow rapidly during this period. The current property climate, with record office and retail vacancy rates, provides the perfect environment for TGG to grow their footprint and take advantage of attractive lease terms.

Clustering of gyms prevents new entrants – Clustering refers to the process of opening several sites in close proximity to one another. In doing so, operators are able to prevent other gyms from opening nearby, understanding that the competition for members would damage returns for them both. This tactic, known as fortressing, creates a dense network of sites that is very difficult for other operators to infiltrate.

Tacit understanding between Gym Group and PureGym – The UK low-cost gym market, dominated by TGG and PureGym is a classic duopoly. Whilst this initially raised concerns about the nature of competition between these two operators, I believe there are multiple signs of tacit cooperation between these two operators. Firstly, these two companies tried to merge in 2014, but were stopped by the CMA because of concerns about anticompetitive practices. Both operators also exhibit signals of tacit cooperation, including mimicry of pricing decisions, rational behaviour towards site selection and using public platforms to signal cooperative intent.

Expertise in choosing the right location – Choosing the correct locations for new sites, and not overpaying for them, are the most important aspects of running a successful gym business. TGG has significant expertise in this area, with access to advanced technology and people with experience in this area, this provides them with a significant advantage over smaller competitors.

Decentralised operating model – The group’s decentralised operating model is a key aspect of their success. Site managers are given the freedom to run their individual gyms and are heavily incentivised depending on performance. Decisions that benefit from the group’s scale such as the buying of equipment, or those that benefit from the expertise of senior management such as site selection, are taken care of by the group. This allows the business to remain agile at the individual business unit level but also benefit from the advantages of being part of a larger publicly listed group.

Evolution of the proposition – As TGG continues to grow, so too do the benefits of scale. TGG is reinvesting these benefits into improving the gym experience, with newer equipment and enhanced spaces. These newer gyms are more akin to the current mid-market offerings and should allow TGG to appeal to a new segment of gym goers.

Investment Thesis

Growing percentage of the UK population are gym users

According to the State of the UK Fitness Industry Report 2025, there are now 11.3 million gym members in the UK, a penetration rate of 16.6%. This number has grown consistently over the past decade, with member numbers in 2014 of 8 million, and a penetration rate of 13.2%. This growth is being driven by a number of consumer trends which are likely to become increasingly prevalent over the coming years.

The first of these is an increasing understanding of the importance of exercise, both from a physical and mental point of view. Evidence of this can be seen in the increasing percentage of the population who are exercising for at least 150 minutes every week; now at 63.7% compared to 42% in 2016. A number of consumer surveys report that mental health benefits are a key factor in driving people towards increased activity levels, closely followed by the desire to get in shape.

Nowhere is this effect more evident than in younger generations. According to research commissioned by The Gym Group, 62% of Gen Z exercise at least twice per week. There are also differences in the way they use gyms, with 23% citing socialising as a key reason behind exercising, and 27% seeing it as a way to meet new people. Lower levels of alcohol consumption and increased health awareness are pushing people away from pubs and towards gyms. If we look at respondents between the ages of 16-34, there are close to double the number of gym memberships than the next age category (47.5% vs 27%).

Source: UK Active Report 2025

The final driver is social media, and the way that has affected perceptions surrounding body image. The growing understanding of the importance of being fit, rather than just thin, is a significant driver for the gym market. This has led to a shift away from cardio-based exercise and towards strength training, which requires access to a gym. This shift is particularly prevalent with the younger generations who have greater exposure to social media and the impact of so called ‘gymfluencers’.

The scope for further membership growth in the UK remains significant, with the US and some of the Nordic countries currently supporting penetration rates of close to 20%. Beyond that, the trends we have looked at above are likely to become increasingly prevalent. Understanding around the importance of exercise is likely to only increase, particularly as the benefits become increasingly understood. Moreover, as older generations (who are less likely to be members of a gym), are replaced by younger generations, the potential penetration rate is likely to be in excess of 25%.

Low-cost gyms are driving growth across the sector

The growth in the UK gym market is being driven primarily by the low-cost sector, particularly when we look at it from a membership numbers perspective (as opposed to market value). Looking at the below graph, we can see that the growth in the mid-market and high-end operators (referred to below as ‘rest of market’) has been roughly static over the past 12 years, with the majority of growth coming from the low-cost segment.

Definitions of low-cost can vary depending on where pricing thresholds are set. The Gym Group’s analysis of Leisure DB’s State of the UK Fitness Industry Report excludes certain operators that they deem not to be truly low-cost but does include public sector operators. The net effect is similar; low-cost gyms members are making up a greater proportion of total members than before, 28% based on 2024 data.

Source: TGG 2024 Annual Report

This growth is leading to a bifurcation of the market, with low-cost operators offering a ‘no frills’ gym experience at one end of the market, and high-end operators such as Third Space at the other end. Trapped in between are mid-market operators like Fitness First and Virgin Active, both of which have struggled to justify their higher membership fees amidst pressure from low-cost competitors.

The activity in the mid-market segment over the past 15 years supports this. LA Fitness and Virgin Active have both had to rationalise their estates, with LA selling its portfolio of London sites to PureGym and Virgin offloading several of their gyms to Nuffield Health. Fitness First nearly went into administration in 2012, and Bannatyne’s has repositioned itself as a wellness club to cater to the premium segment of the market.

Ignoring the top end of the market, which clearly attracts a very different customer base to The Gym Group, there are a number of factors that are driving growth in the low-cost area. The first is what the group calls a rise in the ‘no frills’ gym experience, driven by consumer preference for value for money. The Mintel report covering the sector also states that 70% of people who use health clubs or leisure centres only use the gym, so consumers are increasingly unwilling to pay extra for additional facilities such as pools or saunas.

With the exception of cost, the most important factor for consumers when choosing a gym is proximity. Studies have shown that people are far less likely to visit a gym if it is more than 20 minutes away, with propensity to visit increasing as proximity does. Given low-cost operators now make up a significant percentage of the gym landscape, the closest gyms for consumers are now disproportionately more likely to be low-cost, driving further growth in this segment.

Another reason for the success of low-cost operators relates to the differences in attitude towards exercise between generations. As we have looked at above, younger generations are both more likely to exercise and nearly twice as likely to have a gym membership. Given that these members also have lower disposable income, low-cost gyms are a natural solution. If we look at the breakdown of the TGG membership base compared to the generational splits in the UK population as a whole, we can see that Gen Z and Millennials make up 82% of the TGG member base, compared to 40% of the UK population. Whilst I don’t have this data across the UK low-cost sector, the results are likely similar.

Source: TGG 2024 Results Presentation

The growth in the UK low-cost market is being driven by two operators, The Gym Group and PureGym, who now make up over 80% of this segment. We will look at these two operators in more detail later on, but the low-cost, high-volume nature of this segment of the market means that scale advantages confer disproportionately to the largest operators.

Significant white space for low-cost operators

One of the biggest risks facing the gym sector as a whole is capacity. This risk is most prevalent in the low-cost segment because of the speed at which these companies are expanding their footprints. Overexpansion and excess capacity will drive down individual site returns and impact the unit economics of gym businesses. Determining how much growth there is left in the market is challenging however, but there is general consensus that this is still some way off.

A recent PWC report from indicates that there is still significant white space in the market, with the potential for a total of 1350-1600 low-cost gyms. Based on the most recent number of low-cost gyms, this would imply a headroom of between 550-800 more openings. Whilst this report has been commissioned by The Gym Group, and we should therefore be wary of bias, the logic behind these estimates seems reasonable.

One of the ways operators have been able to maintain such aggressive new opening rates is through the broadening of catchment areas. Looking at a comparison between 2019 and 2023, the percentage of catchments with fewer than 100,000 people has increased by 10% (from 43-53%). Part of this is driven by the fact that as more sites open, the majority of catchment sites with larger populations have already been taken. Low-cost gyms also don’t need huge catchments to be viable, which is evidenced by the clustering of gyms in places such as Brighton and London.

We will look at clustering in more detail later, but there is also potential for greater clustering of sites, particularly within big cities. McFit, the leading German low-cost gym operator, had 8 sites in Berlin in 2008, now they have well over 30, all of which are successful. The population density in big cities such as London means there is potential for a far greater number of sites than currently exists.

Another source of potential growth for the low-cost sector is the change in age demographics within catchment areas. Given younger generations’ greater affinity with the gym, as these cohorts grow up and replace older generations, the size of catchment areas required for gyms to be viable will shrink, driven by the increased density of potential members within these areas.

Finally, there is the potential for low-cost operators to take further share from the mid-market segment. Whilst this trend has been taking place for some time, increases to the national living wage and greater employer national insurance contributions, are likely to create additional pressure. Price increases intended to offset changes to the cost base could drive more consumers towards the low-cost segment. Meanwhile, the evolution of low-cost gyms will likely lead to an erosion of the mid-market’s relative value proposition, but we will look at this in more detail later on.

Company Specific Factors

How The Gym Group, and other low-cost operators, are able to offer far lower prices.

It makes sense now to look in a little more detail at how these low-cost providers are able to offer far lower headline prices than their mid-market competitors. Whilst we will be looking specifically at TGG, several of these factors also apply to PureGym, TGG’s closest competitor, as well as a number of the other operators in this area.

Whilst prices vary depending on location, the average headline rates for mid-market gyms are around £47, whereas for low-cost these are closer to £25. In order for these low-cost operators to be able to offer these prices, they must keep both the initial fit-out costs and the ongoing running costs well below their competitors. One of the biggest ways that they do this is through the removal of unnecessary features such as food courts and especially wet facilities such as pools and saunas. Both of these are very expensive to build, but they are also expensive to run, both from an energy and staffing perspective.

The Gym Group also keeps costs down by operating a far leaner staffing model. Their onsite staff cost as a percentage of revenue is roughly 6%, compared to closer to 25% for many of their competitors. Sites will have a manager and assistant manager, as well as a team of personal trainers who are on part time contracts and generate additional income by training clients using TGG’s facilities. By investing heavily in technology (90% of member sign-ups come through the website), they are able to keep staff requirements to a minimum. TGG is also exploring the opportunity of having multi-site managers as gyms become more clustered, in an effort to further drive down this cost.

No contract and flexible memberships are a key differentiator for the group and another way they are able to reduce costs. TGG estimates that their flexible membership options drive 3 times the volume of members per site compared with contract gyms. This is due to the fact that customers with no-contract memberships visit less frequently, enabling TGG to increase the total volume of members per site. The lower price is also a factor here, with members of premium gyms such as Third Space experiencing much higher visit frequency compared to low-cost operators; 3+ times per week compared to 1.5 times for TGG.

The final factor that allows TGG to offer such low prices is they are open 24 hours a day. This allows them to utilise their assets much more effectively, with shift workers using the facilities during off peak hours and helping to spread capacity. This is not possible at a high-end gym, where the majority of member work normal hours and the gym is closed overnight.

Advantages of scale for low-cost operators

One of The Gym Group’s biggest competitive advantages is its size. As the second largest operator in the market, it is able to exploit these scale advantages and offer lower prices to consumers in return.

The area where this is perhaps most evident is in terms of the group’s buying power. The group operates a decentralised model, but all buying decisions are made centrally, allowing the group to take advantage of its scale. Average fit-out costs for a new site are now £1.3mn, £150k less than 10 years ago. According to the founder this is primarily due to the group being able to negotiate far better volume discounts on items such as gym equipment and lockers. The group is also constantly replacing old equipment as well as fitting out new gyms, so they buy a large volume of equipment throughout the year.

The next benefit afforded by scale is the ability to negotiate more attractive lease terms. The group’s size, as well as the fact that it is publicly listed, gives it greater covenant strength. This means it gets access to better locations, is able to secure more attractive lease terms, and can negotiate longer rent-free periods or greater capital contributions. Securing the best sites and ensuring that you don’t overpay for them is one of the most important aspects of running a successful gym, so the importance of this aspect cannot be overstated. In addition, the greater covenant strength afforded by being a PLC is one of the few differentiators between The Gym Group and PureGym.

“We’re seeing some real benefits from the IPO process. I mean obviously as part of that a lot of the money we raised has been used to pay down debt, so we have by far the strongest covenant in the sector and that’s helping us to secure some of the best sites in the UK” John Treharne, CEO

The next benefit of scale is the ability to offer multi-site access. The Gym Group offers this through its ‘ultimate’ membership package. Roughly a quarter of gym goers use multiple gyms, so this is a compelling value proposition and a key differentiator to other smaller operators. TGG earns an additional £6 on the ultimate membership which is roughly a 100% increase on the margin it earns from a standard membership.

Marketing is another area where the group sees significant advantages of scale. Their marketing budget can be split between two areas. The first is the site level marketing which is controlled by the gym manager. Generally, this is done in the leadup to new sites opening and focuses on local activation. The second type is the group level marketing, which includes TV advertising, and is managed centrally. This is something that the smaller operators are unable to compete with and is a key advantage of scale for the group.

The final advantage of scale for The Gym Group relates to its technology spend. TGG invests millions of pounds every year in its technology, enabling it to reduce costs whilst improving the customer proposition. A good example of this is their website. 94% of members join online, allowing the group to significantly reduce its staffing costs compared to their competitors. Another example is the investment they have made in their mobile app. Customers can use the app to sign in, build workouts and track their progress; again, this reduces the need for costly staffed receptions whilst providing more value for the customer.

Availability of attractive ex-office and retail spaces

One of the key factors in The Gym Group and PureGym’s success was their ability to capitalise on the abundance of attractive units post 2008. This, combined with the well capitalised nature of the two operators meant they were able to secure a number of sites on good terms. This gave both operators a strong foothold in the market and a base for future success. I believe there is a similar opportunity now for The Gym Group (and therefore PureGym) to increase its footprint and take greater market share from smaller operators.

The trend in increasing retail vacancy rates has been taking place for some time, driven by the rise in ecommerce, the failure of certain high-street chains, and the rising business rates in city centres. Current vacancy rates stand at 14-15%, above their long-term average of 11-12%. This is particularly true in smaller towns or secondary high streets.

The same can be said for office spaces post-pandemic. The increased adoption of hybrid working patterns has reduced the long-term demand for office space, particularly for older, lower spec stock. Current vacancy rates in Central London are now between 8-10%, significantly above their long-term average of 5-6%.

Office and retail units possess many of the features that The Gym Group looks for when deciding on new gym spaces. They are generally well connected in terms of transport links, with TGG preferring out of town units with ample parking or city locations with good access to public transport. They are also located in visible locations with good footfall, and their fit-out costs are lower than other units as they generally already have water and electricity.

Gyms are also popular with landlords because of their ability to act as ‘portfolio stabilisers’. By attracting multiple visits per week, gyms increase the overall footfall for a site and increase the attractiveness of other units as a result. The Gym Group’s strong covenant strength also makes it a low-risk option for landlords during a period when they are likely to be more risk-averse.

TGG has plans to roll out an additional 50 sites over the next three years, capitalising on this availability of attractive units. They have also already reported spending an increasing amount of time converting retail space into new gyms, a trend I expect to continue for the foreseeable future.

Expertise in choosing the right location

We have already discussed why choosing the right location (and not overpaying) is the most important factor when choosing where to open a new site. Potential sites need to have large enough catchment areas to make the site economically viable, as well as ensuring that there is sufficient distance between themselves and competitors. Failure to do so will result in the gyms cannibalising each other’s business through excessive pricing competition and driving down site level returns as a result.

The Gym Group does a huge amount of due diligence before choosing to invest in a site, something that I believe creates a barrier to entry for other smaller competitors. Firstly, TGG has a broad site sourcing pipeline which takes advantage of local and national agents, landlords, developers, and ‘bigbox’ retailers. This gives the group greater access to potential sites than a smaller independent gym would have.

They then use spatial modelling to perform catchment testing, with the software used to determine population density, demographics and competition. This is clearly a big advantage over smaller operators who are unlikely to have access to this level of technology. This also significantly reduces the risk involved in opening a new gym, with the ability to test the viability of new sites before significant investment has been made.

The final area where the group excels in terms of site selection is their ability to hire people with experience in this area. Apart from choosing the correct locations, there is a lot of complexity involved in opening a new site. Gyms either need rent-free periods or capital contributions in order to be economically viable during the initial fit-out period. Then there are questions over the structuring of leases, with decisions regarding inflation clauses and open market reviews. TGG have their own Chief Property Officer, with experience managing the store roll-out for Aldi, again something that smaller competitors would be unable to compete with.

Clustering of gyms prevents new entrants

The term clustering refers to the opening of several sites in close proximity to one another. For high-end or independent gyms, clustering is a double-edged sword. Competitors opening nearby puts additional pressure on gyms to differentiate themselves, but it also increases total footfall to an area and is an inevitable part of operating in an urban environment. These gyms also have the ability to differentiate in areas other than price, so competition can actually enhance the perceived value for the customer.

For low-cost operators, clustering, sometimes referred to as fortressing, represents an entirely different strategy. Because these operators compete almost exclusively on price, they are generally unwilling to open a site in close proximity to another low-cost operator, understanding that the inevitable price competition would damage returns from them both. Having a dense network of sites is therefore highly effective at staving off new entrants and maintaining returns for the incumbent operator.

Implementing this strategy successfully is not easy. The trick is to open enough sites to take advantage of the total potential catchment area, whilst not cannibalising customers from your other gyms. Despite this, we have already seen that there is the potential for a far greater number of sites in densely populated urban areas than might be expected. The Gym Group currently has approx. 50 sites in Greater London and believes there is still potential for more; this is also against the backdrop of openings for other operators, particularly PureGym.

The effectiveness of this strategy is difficult to prove given that very few low-cost operators make the mistake of opening near to a direct competitor. Despite this, TGG says there are multiple examples of mid-market operators such as Energie and Anytime Fitness opening nearby and having to close shortly after.

Tacit understanding between The Gym Group and PureGym

Nearly everything I have said so far about The Gym Group could be said for PureGym. The two companies are nearly identical, both in terms of the prices they charge and the way in which they operate. They even attempted to merge in 2014, but the potential move was blocked by the CMA. Initially this raised concerns for me about the nature of competition between them, assuming that these two businesses would resort to competing on price. The more I have researched these two companies, however, the more I believe there is tacit cooperation between them.

The first area where this is evident is in site selection. Operators of both The Gym Group and PureGym will never open a site in the same catchment area as one another. Whilst this could be interpreted as a tacit understanding to avoid encroaching on each other’s territory, it does also represent a rational, independent decision by each operator. Given the significant capital investment required to open a new site, it would be a highly risky decision to open near to a competitor. The incumbent, which is likely to be on a long lease and has already invested significant capital in the site, will defend its position aggressively, likely through lowering prices, driving down returns for both sites. The incoming operator, who must take customers from the incumbent, would also have to spend more money on marketing than an untouched catchment area. This is exactly what makes clustering of gyms is so effective at staving off competition.

The other area where this is evident is in both companies’ pricing strategies. Average headline prices for TGG were £21.49 in 2022, £23.16 in 2023, and £24.53 in 2024; PureGym’s average prices were £25.14, £25.94 and £27.10 for the same three-year period. In terms of percentage, TGG increased its prices at a slightly faster rate, perhaps due to its lower initial prices requiring greater increases to offset the effects of inflation, but the difference was not significant. More importantly, both operators exhibited similar, rational decisions in an inflationary environment.

The other thing to note here is that TGG’s average rate is slightly below that of PureGym’s. This is simply the result of PureGym having more Central London gyms, having acquired a number of sites from LA Fitness, and the higher prices charged at these locations. As an example, PureGym’s most expensive location is £49.99 for its Clapham gym, whereas their Manchester gym is £17.99.

For these reasons, and despite their similarities, I think this is evidence that both The Gym Group and PureGym are able to operate side by side in the same market. Management of each company are complementary of each other’s businesses, and there are public acknowledgements that price competition would be damaging for them both, a common indicator of tacit collusion. The only question here is how long this lasts once the market for low-cost gyms has become saturated.

“I think the best way of describing it [competition] is we’ve got good and capable competitors, but everyone is taking economically rational decisions at the moment, both in terms of headline rates… and also I think in terms of site selection” Luke Tait, CFO

Land grab between The Gym Group and PureGym

Competition between the two largest low-cost operators, The Gym Group and PureGym, has been described by some people as a land grab. Given the limited number of viable catchment areas, there is great incentive to move fast and capture as much of the potential market as possible.

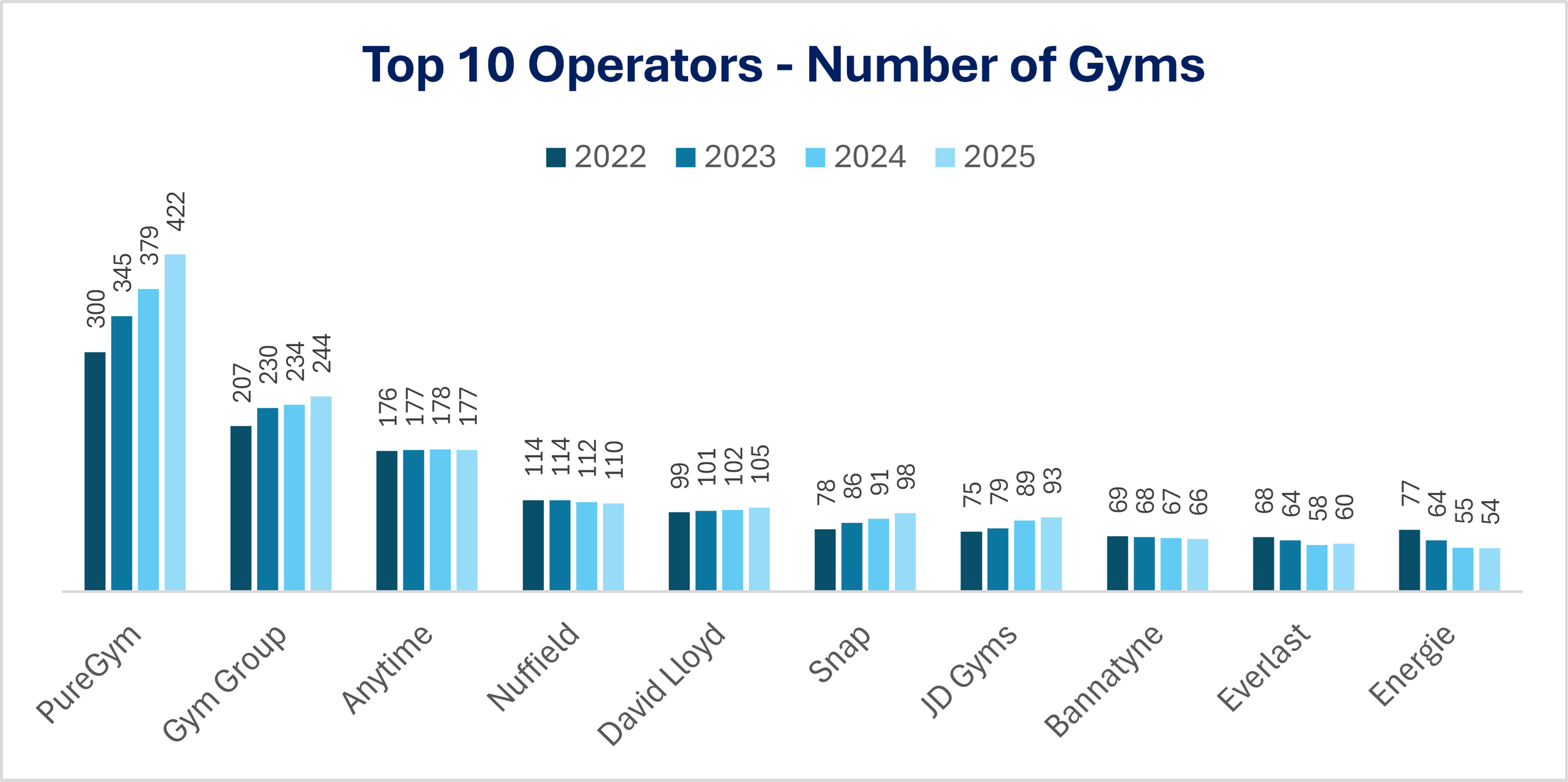

This is why both TGG and PureGym have been expanding their rollout of new sites recently. According to data from Leisure DB’s 2025 report (which differs slightly from the company published figures due to timing differences), PureGym opened 45 gyms in 2022, 34 in 2023 and 43 in 2024; The Gym group opened 23, 4 and 10 respectively.

The Gym Group’s slower pace of new site openings in the last two years is the result of a strategic change for the company. TGG has focused on enhancing returns from their current sites and reducing leverage, with the intention of reinvesting the improved cash flow into new locations. This, combined with a new 30% ROIC threshold for new sites, means they are being far more selective about new locations.

“He told me that for every site we do we turn 30 away. So yes, we’re very interested in growing, that’s where we believe we’ll drive value, but we’re not interested in growth at any cost.” John Treharne, CEO

This highlights one of the main concerns I have about TGG compared to PureGym, and that is that they seem to be losing the land grab. PureGym is jointly backed by PE firms LGP and KKR, with the latter investing approximately £300 million for a 30% stake in the business. PureGym is therefore well capitalised and expanding its footprint rapidly. This may not necessarily be a bad thing for The Gym Group, who may be comfortable as the second largest operator. Given the benefits of scale in the low-cost model, however, it is definitely a risk.

The Gym Group has plans to open 50 new sites over the next three years, and has already opened at the top end of this guidance for 2025. This indicates that the group’s organic rollout strategy is beginning to take shape, but it does leave TGG firmly as the second largest operator with little chance of catching up.

There are two potential positives for The Gym Group. Firstly, PureGym is now looking to expand internationally and may take its eye of the UK market as a result. PureGym acquired Blink Fitness in October 2024, taking on 67 of their sites in New York and Jersey. Given the competitive nature of the US low-cost market, this may prove to be a costly mistake for them and an opportunity for TGG to take UK market share. The other aspect is that The Gym Group’s more selective approach towards site selection may give it improved long-term unit economics. Whilst I can’t comment on the quality of the sites that PureGym has acquired, the speed at which they are expanding suggests that their return hurdles are likely to be lower than that of The Gym Group.

Decentralised operating model

One of the most interesting aspects of The Gym Group is their decentralised operating model. A lot is made of this method of operating, so I am always wary of executives who mention it. This is partly because it is often used as a marketing tool, but also because there are right and wrong ways for it to be utilised.

In the case of The Gym Group, this model works well. Individual sites have their own manager and assistant manager, who take care of the day to day running of the gym. These managers are generally hired in the lead-up to the new site opening and are given a say as to the layout of the gym and its equipment, as well as how they would like to market the opening at a local level. As such, TGG tends to hire higher quality local managers than their competitors, generally paying above average market rates.

Decisions that benefit from the group’s scale, or concern the group as a whole, are made centrally. The purchase of gym equipment, both for new sites and to update existing gyms, is done centrally, where the group can benefit from its greater buying power. Decisions around expansion of the group’s footprint and the opening of new sites are also controlled centrally.

In order for the model to function effectively, the group also incentivises local managers. Managers are judged on metrics such as revenue, profit, or return on capital, and receive bonuses both quarterly and annually. The quarterly bonus structure is something that management believes helps to align the bonus more closely with good performance.

I think this model suits The Gym Group really well. It gives site level managers the flexibility to make faster decisions and run more agile business units as a result; at the group level they are able to take advantage of their scale and greater resources.

Evolution of the proposition

I think one of the most exciting things I have seen about The Gym Group is how their proposition has evolved over the last few years, and how they are looking to continue to develop this. One of the advantages of being a scale operator is that the larger you grow, the greater the benefits of scale become. These lower costs can then be returned to customers in the form of lower membership fees or reinvested to create a better value proposition for customers, further strengthening the barriers to entry.

The original gym group sites were what you would expect from a low-cost gym, repurposed warehouses without much retrofitting. The new openings are a significant upgrade on this, with high quality equipment and sites that look far more similar to the mid-market offerings from TGG’s competitors. The group’s plans for their newer sites expand on this even further and move these sites into more direct competition with the mid-market segment, but at much lower headline rates.

There will always be a gap between the top end of the market and TGG, and I expect this continued evolution of TGG’s value proposition to lead to even greater bifurcation in the market. The enhanced low-cost sites have the potential to offer what the mid-market does, without the addition of unnecessary areas such as wet space. Whilst the emphasis will always be on low membership fees, the enhancement of the gym experience has the potential to attract an entirely new segment of the market.

Risks

Saturation of the UK low-cost market – This is the number one risk facing The Gym Group, particularly given that several of their competitive advantages are specific to their domestic market. That said, there are a few factors that I think point to significant headroom in the UK market. Firstly, currently 28% of UK gym goers are members of a low-cost gym; in some Scandinavian countries this is closer to 50%, so there is still significant potential for growth in this area. Secondly, there is the potential for a growing percentage of the UK population to become gym users, something that seems likely given the greater propensity towards gym use in younger generations. There is also the potential for population growth in the UK, although this is forecast to be insignificant and predominantly driven by inflation.

Although not specific to the UK, there is also the potential for expansion into other countries. The Gym Group has mentioned placed such as Australia in the past, so there are other possible sources of growth once the UK market has become saturated.

Price competition from other low-cost competitors – Given we have not yet reached saturation in the UK market, low-cost operators have been able to grow without cannibalising each other’s business or competing directly on price. Once the market has reached its ceiling, however, there is a possibility that gyms resort to competing solely on price, damaging returns for each of them as a result. The outcome of this is difficult to predict, given it depends on the rationality of the management from each business, but the current signs have been positive.

Foreign operator entering the UK market – Whilst this is always a risk, I don’t think the likelihood of it happening is significant. When TGG talks about the international markets it would look to target, somewhere like the UK, which has two large incumbent operators, would be pretty close to bottom of its list. An incoming operator would likely have to run at a significant loss to just to be competitive on price and would lack the specific market knowledge of any of the domestic gyms.

Valuation

TGG is a relatively challenging business to value for a number of reasons. Firstly, the changes to accounting conventions, in particular the introduction of IFRS 16, means that historical margin rates provide little guidance on potential future ones. The business is also currently earning a return below its cost of capital and requires some aggressive assumptions around margin expansion and required levels of reinvestment to make the company value creating. Finally, whilst the business provides guidance on the return hurdles for individual sites, there is no guidance on what that might look like once the gym portfolio has reached maturity. Given the business has been in an almost constant investment cycle throughout its public market history, there is also little guidance from historical figures either.

That said, the nature of the revenue model does lend itself well to the forecasting process. The majority of revenue is in the form of membership income, which is a function of the number of sites, the average number of members per site, and the average income per member. This brought up another issue for me in terms of the valuation; the fact that despite the overall market potential for approx. 500 more sites, the group is limited in its domestic growth, particularly within the terminal value period.

My base case scenario assumes new site openings at the mid-end of management guidance. Margins expand and move in line with longer-term (pre IFRS 16) levels. Required re-investment could be slightly overly punitive, but the required level of investment given the number of new site openings needs to be taken into consideration.

The bull case scenario assumes new site openings at the top end of management guidance. Margins expand to levels higher than previously seen and required reinvestment drops throughout the forecast period, bringing return on invested capital above any level seen historically. Whilst this is not impossible and in reality could be driven by the portfolio of sites reaching maturity, the level of assumptions required in this case makes me uncomfortable giving it a higher probability weighting than 40% (even that to me seems very generous).

I have not included the bear case scenario in my probability weighted estimate as the value is negative.

Conclusion

This is another one that has failed the valuation hurdle for me. Whilst the business itself is really interesting and has some compelling competitive advantages, the valuation is challenging to get past. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that the group’s previous largest shareholder, Blantyre Capital, has significantly reduced its stake recently. Either way its not a buy for me at the current price.